History

The history of East Maui, specifically Honomanu, holds significant cultural, environmental, and historical value. Located along the rugged northeastern coast, Honomanu reflects the heritage of Native Hawaiian practices in land stewardship, agriculture, and water management. Traditionally, the area was known for its kalo (taro) farming, which was essential to the Native Hawaiian diet and culture. The complex network of lo‘i kalo (taro patches) cultivated in Honomanu was part of a larger ahupuaʻa (land division) system that integrated resource management from the mountains to the sea, emphasizing sustainable practices and respect for natural resources.

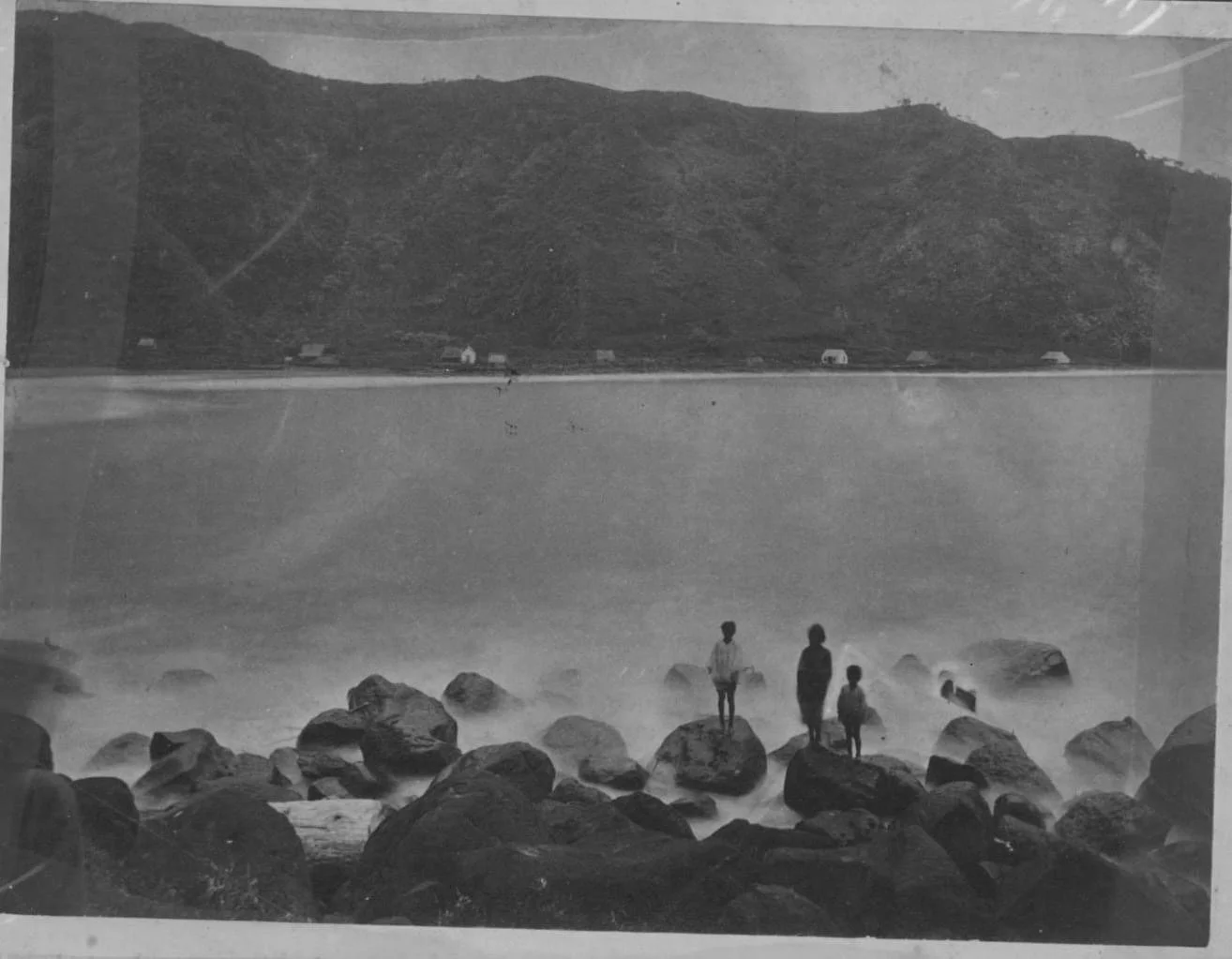

Honomanu Bay and its surrounding lands were not only agriculturally productive but also held spiritual significance. Many wahi pana (sacred places) in this area are linked to Hawaiian legends and practices, and they represent the deep relationship between the people and the ʻāina (land). These practices also reflect a profound understanding of the watershed and its importance in sustaining communities and ecosystems.

Today, Honomanu’s history remains essential for the preservation of Hawaiian cultural identity and the protection of the natural environment. As modern conservation efforts emphasize water rights and watershed management, understanding Honomanu’s historical agricultural practices and land use offers insight into sustainable management practices that honor Hawaii’s cultural heritage.

Traditional Kalo Farming

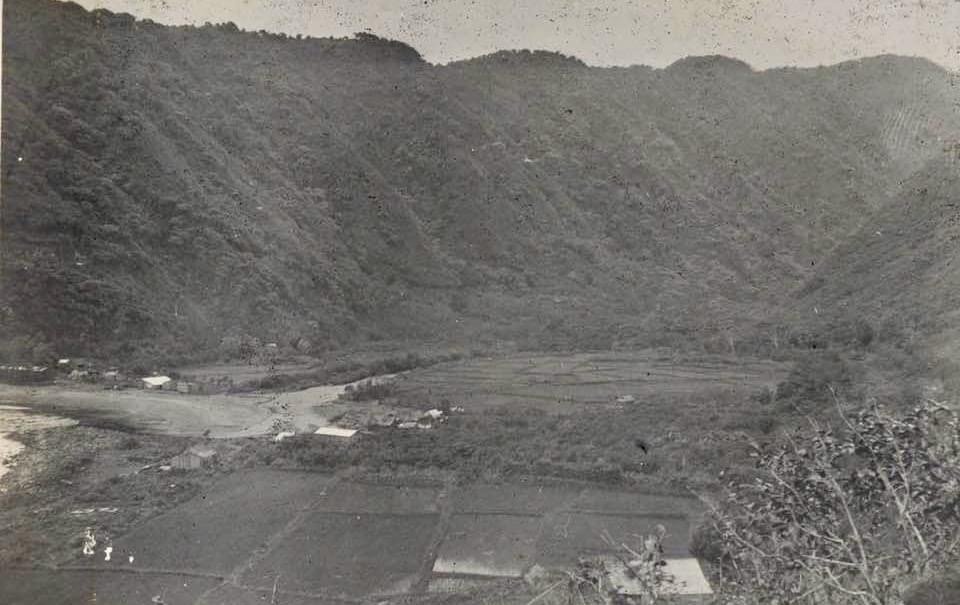

Restoring kalo (taro) farming in Honomanu is part of a larger movement to revive traditional Hawaiian agricultural practices, promote food security, and restore ecosystems. Historically, Honomanu was home to extensive loʻi kalo (taro patches), which were skillfully managed by Native Hawaiians using the ahupuaʻa system. This traditional land division and management system ensured that resources, especially water, were carefully allocated from mountain streams to the sea, supporting both agriculture and native ecosystems.

Restoration of kalo farming here involves the rehabilitation of ancient loʻi terraces, as well as the re-establishment of irrigation ditches and ʻauwai (water channels) that direct stream water to the fields. This work not only honors the legacy of Native Hawaiian ancestors but also reintroduces kalo as a staple crop, benefiting local diets and offering an economic boost through poi and other value-added products. Importantly, kalo restoration efforts strengthen the cultural identity of the community and provide hands-on opportunities for younger generations to learn traditional farming methods.

Additionally, restoring kalo fields supports environmental health in Honomanu. Loʻi kalo systems naturally filter water, reducing sediment and nutrient runoff to the ocean, which benefits downstream marine life, such as coral reefs. The cultivation of kalo also encourages native biodiversity by creating a habitat for native plants and species adapted to wetland environments.

Through community-driven efforts, kalo farming restoration in Honomanu represents a vital connection between cultural heritage, sustainable land use, and environmental stewardship. These efforts provide a living classroom, empowering communities to uphold the Hawaiian values of mālama ʻāina (caring for the land) while promoting food sovereignty in East Maui.

Honomanū Homesteads

The homesteading history of Honomanū in Koʻolau, East Maui, reflects a time when Native Hawaiians and settlers sought to reclaim and cultivate land, adapting traditional practices within a modern framework. This region, historically known for its abundance and significance within the ahupuaʻa land management system, was crucial for agriculture, particularly in kalo (taro) cultivation, which sustained communities for centuries.

In the early 20th century, as Hawaii’s government initiated homesteading programs, lands in Koʻolau and other parts of East Maui were designated for Hawaiian homesteading under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920. This Act, designed to provide land for Native Hawaiians of 50% or more Hawaiian blood, aimed to promote self-sufficiency by giving Native Hawaiians access to lands for agricultural and residential use. Koʻolau was one of the regions with available lands, though the challenging terrain and limited infrastructure made farming difficult, and many families struggled to establish sustainable homesteads in the area.

Despite these challenges, homesteaders in Honomanū and Koʻolau often revived traditional agricultural methods and maintained cultural practices, such as cultivating kalo in wetland patches. This connected them with ancestral knowledge of land and water stewardship. Additionally, homesteading in this area became a way to resist the pressures of plantation expansion and large-scale land privatization, which had encroached upon Hawaiian lands for decades.

Today, remnants of the homesteading era and restored loʻi (taro patches) in Honomanū connect families with their heritage, serving as tangible links to their ancestors’ knowledge and values. Ongoing efforts to protect water rights, preserve kalo lands, and promote community-based farming in Honomanū and Koʻolau reflect the resilience of the homesteading spirit, underscoring the Hawaiian commitment to land, culture, and self-determination.